What is a Story?

A story is a problem solved.

What is a Story?

This week, as promised, we’re going to define what a story is.

Definitions are tricky because they are inherently limiting. And when discussing something as vast and essential to the human experience as storytelling, narrowing it down to a few words is a challenge. But, who cares, I’ve done it:

A story is a problem solved.

That’s it. It’s that simple.

Let’s consider the evolutionary psychology behind storytelling. It is, without a doubt, the adaptation most responsible for humanity’s dominance on this planet. Storytelling allows us to communicate possibility to one another.

What possibilities?

The possibility of danger.

The possibility of advancement.

The possibility of success.

A story implants a unit of information into someone’s mind—something they can later recall, compare against reality, modify, and extract meaning from to apply to their own life. This is why storytelling is so powerful.

The Structure of a Story

If a story is a problem solved, what does that mean for the storyteller?

First, it provides a clear beginning and end. While stories will, of course, contain characters and settings (which we’ll explore later), the story doesn’t truly begin until the central character—a.k.a. the protagonist—encounters a problem that holds them back from something they want.

That want could be the pursuit of something positive (success, love, knowledge) or an escape from something negative (danger, failure, oppression). Regardless, once that moment happens, your story has begun.

Interestingly, traditional literature studies have not often focused on this precise moment. Academics often analyze the overall arc of a story rather than pinpointing when the story itself actually begins. But this information is vital to the storyteller if they want a compelling tale, without starting too early or too late.

Enter the screenwriters.

Screenwriting, being an industry with intense competition and limited resources, has developed its own terminology to define these crucial moments. Screenwriters have a name for the exact point where a story truly begins:

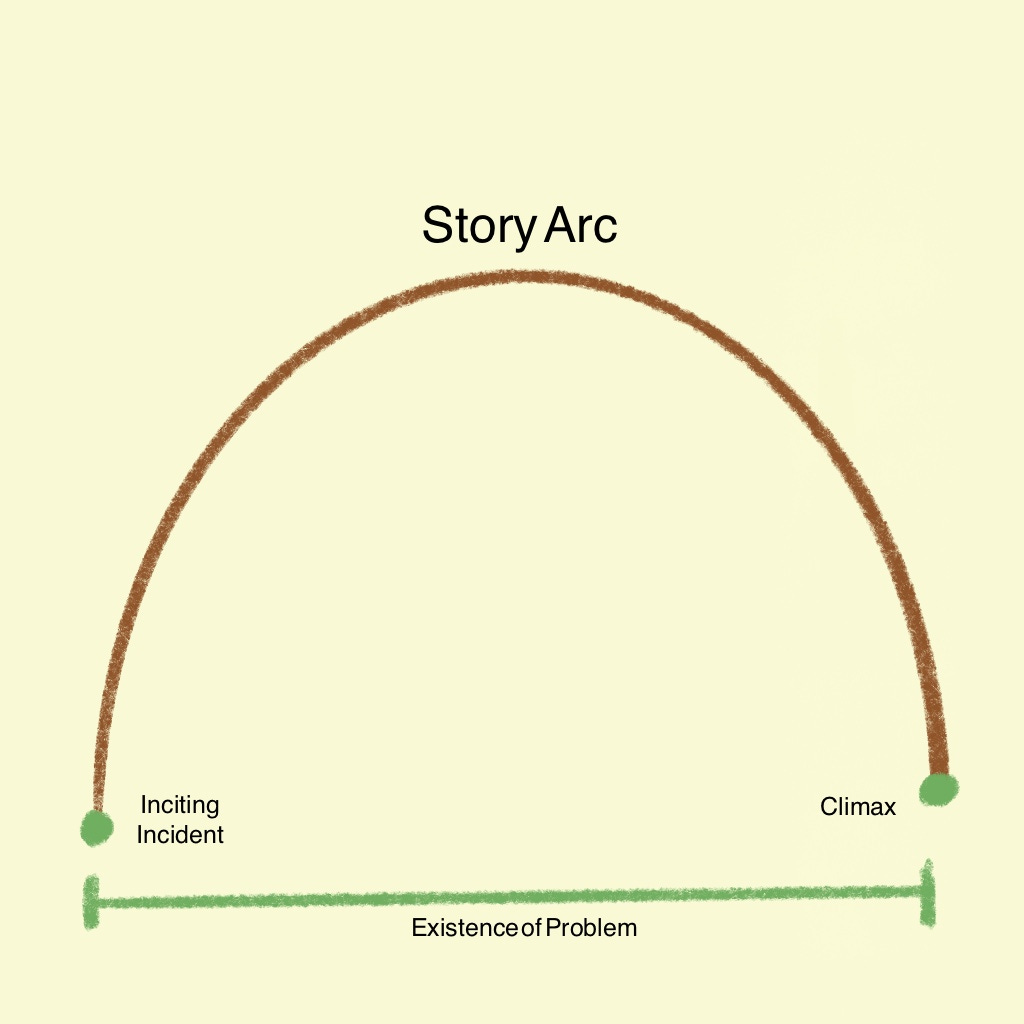

The Inciting Incident

The inciting incident is the moment when the protagonist encounters the core problem of the story. Importantly, this is not necessarily where the story starts being told. A story may begin with exposition, world-building, or even a smaller story leading into the larger one before reaching the inciting incident.

And, of course, storytelling is rarely simple. You can layer escalating inciting incidents, where an initial problem appears solvable—only for the solution to lead to a bigger, more complex problem, and so on.

The Climax

If the inciting incident marks the beginning of the problem, then its counterpart is the climax—the moment when the problem is resolved.

Unlike the inciting incident, the term climax comes directly from literary studies. It’s one of the oldest concepts in storytelling, and yet it’s surprising by how many people misunderstand it. Some believe the climax is simply “the most action-packed moment” of a story. But that conception misses the point.

The climax is the second key moment in the story’s arc—it is directly connected to the inciting incident. If the inciting incident starts the problem, the climax is the moment where the problem is solved.

But, just as a story may extend beyond its inciting incident with exposition and buildup, it also often continues past its climax into the resolution, where loose ends are tied up and thematic conclusions are drawn.

A Story Must Have an End

These two moments—the inciting incident (the problem begins) and the climax (the problem is solved)—form the very essence of a story.

Now, you may have a lingering question: What about stories where the problem isn’t solved?

The answer is simple: a story isn’t over until the problem is solved.

Some narratives may feel incomplete, and that’s because they are—without a climax (i.e. solution), they don’t fully function as stories.

That doesn’t mean they aren’t interesting or worth your time. Many poems and songs are beautiful expressions without climaxes.

At the same time some serialized narratives may veer off course and fail to deliver on early promises. If they still deliver a drip-drop of satisfying episodic climaxes they may run for years or even decades, but the audience will always thirst for closure. It’s this thirst that keeps them coming back. Anything that feels like a story but doesn’t resolve will leave an open wound because the audience didn’t get something they instinctively needed. This can be employed as an artistic effect, or as a marketing ploy.

This doesn’t mean every story needs a happy ending. A tragic ending is still an ending. The protagonist may fail, but this is still a solution. In this case the problem defeats them. Since the protagonist no longer has a problem that they can contend with the story is over. The problem has solved the protagonist.

Either way, the story reaches a conclusion. The problem is gone.

Next week, we’ll explore how stories develop from this basic structure into complex narratives.